One of my favourite tracks on the second installment in the Body Talk series is We dance to the beat, the lyrics of which describe how we dance to the beat of all sorts of wonderful things, such as the beat of the continents shifting under our feet.

I'm a mathematician, so needless to say the line we dance to the beat of false math and unrecognized genius caught my attention. That line was one of the reasons that I listened to Body Talk pt. 2 over and over again (yes, I'm a bit of a geek). Luckily, the album is nothing short of amazing, just like parts 1 and 3, so the listening pleasure was far greater than what I would get simply from hearing a pop star mentioning mathematics.

In what must surely be a future textbook example of synchronicity, the words false math had been stuck in my head for a couple of days when the guys from the digital production company DinahMoe contacted me. As it turned out, We dance to the beat was in need of some real mathematics.

DinahMoe were developing a first of its kind interactive music experience in collaboration with Blip Butique. Released a week ago, it allows users to remix We dance to the beat and create a music video of sorts by combining sounds and visuals on the interactive beat machine site. The users search through a grid of video/sound clips and choose a combination of four videos and four sound clips. They can then interact with the clips to manipulate both audio and video, in perfect sync with the beat.

Users can share their remixes on Twitter or Facebook and look at the ever-growing seamless stream of remixes created by others. Every now and then the stream of remixes is interrupted by pre-programmed mixes with footage of Robyn, making the stream experience even cooler.

So, where do the mathematics enter into all of this? Well, there are 14 basic sound clips in the interactive beat machine and the creative team behind it wanted to construct a grid where each cell in the grid contained one clip. The users should be able find all possible combinations of 4 out of these 14 clips by looking at a subgrid with four cells (as in the picture above). The question, then, is how large the grid needs to be in order to fit all combinations and how the clips should be arranged so that no clip is ever paired with itself.

In order to answer this, we need to find out in how many ways we can choose 4 out of 14 clips. We could do this by listing all possible combinations (clips 1, 2, 3, 4, clips 1, 2, 3, 5, clips 1, 2, 3, 6, ... clips 11, 12, 13, 14), but that would (a) take too long and (b) bore us to death.

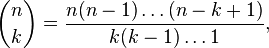

Not having a deathwish, I decided to make use of some tools from the mathematical branch of combinatorics. It just so happens that a classical combinatorial problem is the question "in how many different ways can we choose k out of n objects" (here k and n are whole numbers and k is less than or equal to n).

Luckily, others have solved this problem before us, and we can use their solution right away. The answer to the question can be written as what mathematicians arrogantly refer to as a "simple" formula, using what is called the binomial coefficient (the strange thing on the left hand side in the expression below). The formula is

which in this case, where n=14 and k=4 becomes (14*13*12*11)/(4*3*2*1)=1001. That is, there are 1001 possible ways to choose 4 out of 14 clips.

which in this case, where n=14 and k=4 becomes (14*13*12*11)/(4*3*2*1)=1001. That is, there are 1001 possible ways to choose 4 out of 14 clips.So, we need to create a grid where all 1001 combinations of four clips can be found by looking at a subgrid of size 2*2, that is, a grid with two rows and two columns. The clips much be placed in such a way that, for instance, clip number 1 never is found next to itself in the big grid - when the user looks at four cells there must be four different clips placed in them.

Consider the following small grids. In each of them there are two 2*2 subgrids that the user can look at.

In the grid to the left, the combinations of clips 1, 2, 4, 5 (the four cells to the left in the grid) and clips 2, 3, 5, 6 (the four cells to the right in the grid) are found. In the middle grid, the combinations are 1, 2, 4, 5 and 1, 2, 5, 6. In the grid to the right however, the combination 1, 1, 2, 4 is found, which isn't permitted. That's the kind of subgrids that we want to avoid.

In the grid to the left, the combinations of clips 1, 2, 4, 5 (the four cells to the left in the grid) and clips 2, 3, 5, 6 (the four cells to the right in the grid) are found. In the middle grid, the combinations are 1, 2, 4, 5 and 1, 2, 5, 6. In the grid to the right however, the combination 1, 1, 2, 4 is found, which isn't permitted. That's the kind of subgrids that we want to avoid.Before we try to create the grid, we need to know how large it should be. How many subgrids of size 2*2 are there in a grid with a rows and b columns? Let's look at some examples:

From examples like this we can deduce that there is a general formula for the number of 2*2 subgrids: in a grid with a rows and b columns there are (a-1)*(b-1) subgrids of size 2*2. We need a grid with at least 1001 such subgrids in order to be able to fit all 1001 combinations in the grid.

It seemed reasonable to have a grid where a=b, that is, a grid with the same number of rows and columns. Then (a-1)*(b-1)=(a-1)*(a-1)=(a-1)2=a2-2*a+1. When a=32 we get that a2-2*a+1=961 and when a=33 we get that a2-2*a+1=1024, which is larger than 1001. Thus 33 is the smallest value of a that results in a grid where all combinations of 4 out the 14 clips can be placed.

In summary, we've found that there are 1001 combinations of 4 out 14 clips and that we need a grid that has at least 33 rows and 33 columns if we want all of these combinations to be found in 2*2 subgrids. Furthermore, we know what kind of subgrids we wish to avoid.

At this point, placing the clips in the grid is like solving a massive 33*33 sudoku with a strange set of rules. I did a bit of programming, using my favourite scripting language R, to let my computer do this for us. The resulting grid is one of the hidden cogs that is the magic behind the beat machine.

(To complicate things a bit, the grid we used is "infinite" in the sense that the left border of the grid fits with the right border, so that if you go 34 steps to the right or left, or 34 steps up or down you will come back to the same 4 clips that you started with.)

And then there is the matter of how to place the video clips in the grid... But that's another story.

Robyn recently performed at the Nobel peace prize concert. DinahMoe make awesomeness happen with interactive sounds and adaptive music. Check out their website for more examples!